Ethical jewelry company provides alternative to conflict minerals

This article appeared in the Toronto Star on Monday, September 29. The entire article, by Toronto Star staff reporter, Marco Chown Oved, is shared in its entirety below. Photo by Andrew Francis Wallace, Getty Images.

Peek into the window of the Fair Trade Jewellery Company on Parliament St. and you’ll see display cases filled with gleaming engagement rings.

It’s a view not unlike one you’d find at other jewelry shops in town, but the gold and diamonds here have an invisible but ethical difference — they’re traced all the way from mine to finger.

“We’re purpose-built to eliminate all the worst abuses that occur in mining, from gold that fuels conflicts to the mines that use child labour,” said the shop’s co-founder and lead designer Ryan Taylor. “We work directly with mining communities to improve their practices. We want to lead by example in this industry.”

Not everyone is preoccupied by the origins of their engagement rings, but as awareness of the dangerous conditions and toxic chemicals in mining grows, ethical jewelry is emerging as an alternative.

“We knew a bit about mining,” said Carleen McGuinty, who went to the Fair Trade Jewellery Company with her husband Eric for their wedding bands. “In making this important investment, we didn’t want to look down at our fingers and feel guilty. We wanted it to honour our values and our love for each other.”

While using recycled gold was an option, once they found FTJco, they were thrilled to learn that their rings would be beneficial to Latin American miners.

“It’s a personal connection with the metal in the ring,” McGuinty said. “We’re working toward a better future, through this little thing that we can control.”

At a time when the Canadian government is funding development partnerships with mining companies to ensure that the profits from mining make it back to local people, fair trade gold provides a distinctly alternative path.

The Fair Trade Jewellery Company is the first shop of its kind in North America to visit mines and work directly with miners’ co-ops.

“We pretty much pioneered responsible sourcing through the supply chain,” Taylor said.

But finding and certifying gold isn’t as easy as selling fair-trade coffee. It all started in 2006, when a couple commissioned Taylor to fabricate their engagement ring they asked him a seemingly simple question: “where does the gold come from?”

That inquiry ended up sending Taylor on a half-dozen trips around the world to find out where gold was being mined, and how to make sure that the miners were getting a fair deal.

“I thought it would be so easy. I should be able to pick up the phone and find out. But no; the system is so disconnected,” he said.

Most jewellers get their gold from a few massive refineries that purchase ore from sources all over the world and cannot guarantee its origin. Gold from industrial mines is mixed in with gold mined by small-scale — or “artisanal” — miners, often in dangerous conditions and using toxic chemicals. Once it’s all melted down, there’s no saying where it came from and how it was mined.

“Whatever people purchase, there’s someone on the other end of that,” Taylor said. “Now more and more people want to know who that person is.”

The inquisitive couple had to delay their wedding for a whole year while Taylor travelled to the Oro Verde mine in Colombia, where he met with a co-operative of artisanal miners and learned about working conditions and the challenges facing their community.

He brought along an auditor from the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) and together they set up the first “fairmined” gold purchase: a half kilo of gold brought back to Toronto and made into rings for the first clients of FTJco.

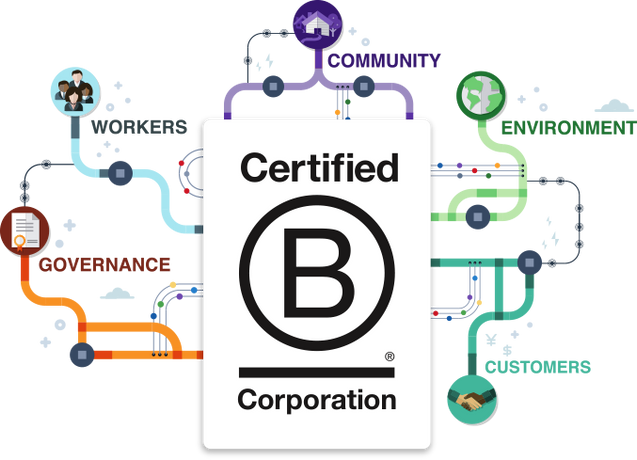

ARM now has a certified “fairmined” standard that guarantees gold is mined following a set of environmental standards and that miners are fairly compensated for their work. Taylor’s business has been at the forefront of that process every step of the way.

The Cabbagetown shop is a bizarre mix of old and new and the process is both low- and high-tech. Like 18th- and 19th-century artisans, he has display cases in the front room and an operational workshop in the back.

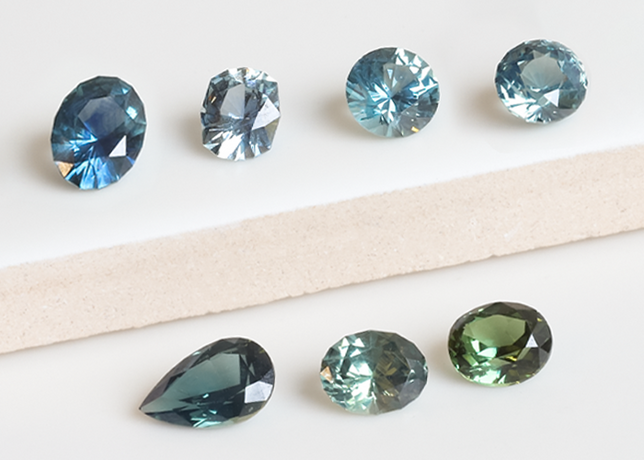

Gold from Colombia, Peru and Bolivia is brought here, where computers and 3D printers are employed to produce custom-made rings on site. But when the rings come out of the digital kilns and moulds, they’re polished by hand with the same tools that have been employed for generations.

Taylor and co-founder Robin Gambhir offer a choice of jewelry made from recycled or ethically sourced gold that’s doubly-certified: both “fairtrade” and “fairmined.” They also use Canadian diamonds, steering clear of any of the complications around “blood” diamonds from conflict zones.

While critics point out that mercury is still allowed by the fairmined certification, Taylor says that outright elimination of the dangerous neurotoxin is impossible in the short term, and in the meantime miners are receiving training in responsible handing.

Like other fair-trade certifications, there remains some doubt over whether environmental and labour standards are maintained at the mines between inspections, but Taylor says he works with the most rigorous third-party auditors and has personally witnessed improvements on the ground.

For his pioneering work, Taylor has been invited to speak about conflict minerals and certification processes to the U.S. State Department when they were discussing new standards included in the Dodd-Frank Act. He’s also worked with the OECD due-diligence committee on conflict minerals.

And yet, after a decade, fair-trade gold is still not a very well known or understood commodity.

“Responsible sourcing is not something customers ask for,” Taylor said. “It’s a difficult conversation to have with customers.”

His company is set up to cut out all the middlemen, so that only people directly involved in producing the ring get paid. If, on the other hand, you buy your jewelry from a regular jeweller, which buys its gold from an industrial mine, huge amounts of money are spent on building and running the mine and profits are funnelled to shareholders.

But Taylor and Gambhir only work with artisanal miner co-ops that they’ve personally visited and have made efforts to understand.

“We provide an outlet for artisanal mining communities who are committed to eradicating child labour, improving environmental practices and investing in the future,” Taylor said.

The miners make more money when they get certified, and instead of scraping out a meagre existence, they’re now sending their children to university to become the next generation of mining engineers, he said.

While Taylor and Gambhir have found success, ethical jewelry remains a tiny fringe of the international gold market. Along with small groups of miners, they’ve have staked their future on the hope that as awareness grows of the environmental impact and social disruption that come from large scale industrial mines, so will demand for another way.

Solitaire

Solitaire

Solitaire with Pavé

Solitaire with Pavé

Bezel Set

Bezel Set

Halo

Halo

Multistone

Multistone

Unique

Unique

Nature Inspired

Nature Inspired

Everyday

Everyday

Wider Band

Wider Band